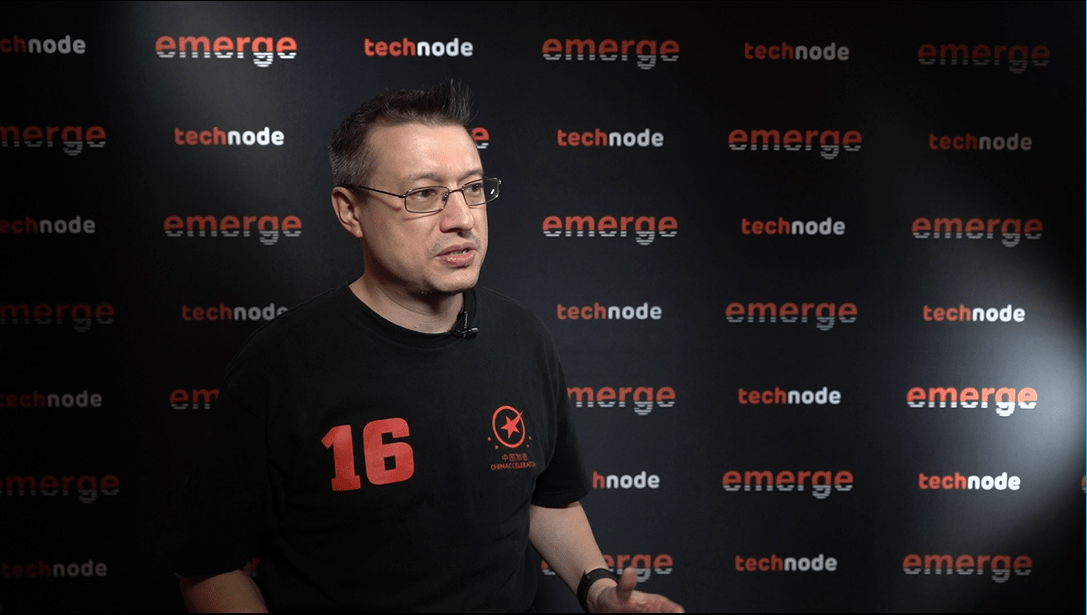

From app bans in the US and India to the Chinese government’s increased push for self-reliance in cutting-edge technologies, 2020 has been a rollercoaster year for China tech. How has China’s VC industry been faring? Last week, TechNode held its Emerge 2020 conference in Shanghai. On the sidelines of the event, we chatted with William Bao Bean, an experienced venture capital investor who has been active in China since 2007.

Bean is a general partner at investment firm SOSV. SOSV runs Chinaccelerator, a startup accelerator based in Shanghai.

We covered some of the biggest questions facing Chinese technology companies in 2020: How much capital is enough to achieve tech independence? How will the country’s Nasdaq-style STAR Market affect funding? What does the slew of Chinese companies delisting from US exchanges mean for VC in China?

VC Roundup

VC Roundup is TechNode’s monthly newsletter on trends in fundraising. Available to TechNode Squared members.

We took the opportunity for an interview. We’ve printed it in full below, edited for brevity and clarity.

TechNode: What are the new trends that you see in China’s VC market this year?

William Bao Bean: There are two major trends. First is enterprise B2B (business to business), where AI is becoming more important. Traditionally, large Chinese companies did not want to pay for their software, but now, one of the biggest applications of AI is personalization. For example, it can be used to tailor the messaging and advertising you see on an e-commerce site to each consumer’s preference. It’s very difficult for startups and other companies to build their own AI systems, because AI scientists are quite expensive to hire, and the big guys like Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu basically hired most of the experts. So there’s actual demand for AI services from companies who want to remain competitive. Since the only way to remain competitive is personalization, companies are willing to actually pay to bring in AI solutions.

Second, there’s a huge amount of investment happening around government policy. The Chinese government is really supporting investments in semiconductors, telecoms equipment, and a lot of hardcore traditional technology. Previously, you saw Chinese companies developing their own solutions. But because of the US-China tech decoupling and the difficulty in sourcing international semiconductors, telecoms equipment, and even manufacturing equipment, you’re seeing massive investment in these areas in China. It is a huge opportunity for local companies, and a very big opportunity for Chinese investors.

TN: Do you think putting in more money will help China catch up with the world’s leading players in semiconductors?

WBB: China’s semiconductor industry is behind. But when you dump money on a problem, generally, you get a solution faster. I still think China is still four to seven years behind, but a huge amount of capital is flowing into the industry, so I think you will see the technology innovation gap narrowing. Often in China, when you have big government backing, there’s a huge amount of opportunity in that space—we’re seeing a huge amount of activity there.

TN: What are the impacts of recent US-China tensions? Are China-based VC firms having a hard time raising money from the US?

WBB: Not so far. In China, VC firms have raised a lot of money from US investors. Now, we don’t know whether future funds will have difficulty raising money from those same limited partners (LPs). A friend of mine just closed a new $200 million fund from big traditional US LPs, and he is focused just on deep tech in China. He successfully closed last month in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic. So far, the early data that we see is that it’s not having an impact. Investors are after returns, they don’t care about politics.

TN: We have seen many Chinese tech companies delist from US stock exchanges and more companies choosing to dual-list their shares in Hong Kong this year. What do you think these trends mean to tech investment in China?

WBB: 2020 has been a record year for Chinese companies listing in the US. When startups are getting bigger, they go where the capital is. It’s still the case that the US is where the higher valuations and the big capital willing to invest in technology can be found.

In China, tech companies that list face a lot of restrictions. For example, they generally need to be profitable. Most technology companies are not profitable for three years —they grow fast and they’re investing money in the future. The restrictions on listing also make it very difficult for Chinese companies to tap global capital markets, so they choose to go abroad. The second thing is that the international appetite for technology investments is much higher than in China. In China, you have a huge interest in consumer-facing companies, but not so much interest in hardcore technology. And so those two issues combine to drive continued interest in an overseas listing.

TN: Shanghai’s STAR Market doesn’t require companies to be profitable to list. How do you think this change in listing rules has impacted investment in China? Do you see increasing competition from RMB funds against US funds?

WBB: Startups just go where the capital goes. Many US dollar funds also have RMB funds. If you’re doing something on the consumer side, RMB funds make sense. RMB investors like investing in Chinese consumer-facing players—products that they can see and feel. For some companies that are not profitable, or require huge amounts of money, and have historically raised US dollars, they have to go the international path. Sometimes you move the company from offshore to onshore, or from offshore to onshore based on where the money is. It’s just a pure market effect. One is not competing against the other. It’s just what makes sense for the company to get the best value to be able to raise the money and then to exit.

Big deals

One of the biggest investments in China’s tech sector in the third quarter went to Yuanfudao, an online education firm. On Oct. 21, the company raised $1.2 billion from investors including DST Global, CITIC PE, and Temasek, valuing it at $15.5 billion.

Ted Mo Chen, a Beijing-based edtech entrepreneur, wrote in a column published on TechNode last month that the Covid-19 pandemic ignited a “unicorns take all” game in China’s online education market—and edtech startups have attracted big checks from investors.

Here are some of the biggest deals in China tech in the third quarter.

- July 23: Meiri Youxian, a grocery delivery startup, raised $495 million from investors including CICC Capital and Tencent, valuing the company at $5 billion.

- Aug. 5: Yipin Shengxian, a grocery delivery company, raised RMB 2.5 billion ($374 million) from Tencent and Capital Today with a valuation of RMB 15 billion.

- Aug. 18: JD Health, the healthcare unit of e-commerce giant JD.com, raised $830 million from Hillhouse Capital with a valuation of $30 billion.

- Sept. 22: Electric vehicle maker VM Motor raised a RMB 10 billion (around $1.5 billion) Series D from investors including state-backed SAIC Capital, Baidu, and SIG China, hitting a valuation of RMB 35 billion.

- Oct. 21: Edtech company Yuanfudao raised $1.2 billion from investors including DST Global, CITIC PE, and Temasek, valuing it at $15.5 billion.